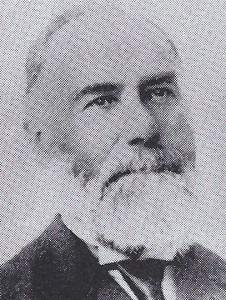

Henry Eyring

(1835-1902)

Genealogists trace the name Eyring back to the time when they accepted Christianity, the meaning of the name being Pagan God of light.

The Eyrings were well-to-do apothecarists. There father, Edward Christian Eyring, invested his fortune in the factory to manufacture an oak extract for tanning leather and after much hard work and experience, it failed, losing all. His son Henry was born March 8, 1834. Family history says this loss to Henry was probably a blessing in disguise, as it was the cause of his sister Bertha and himself migrating to America where they heard and accepted the Gospel. Otherwise, he might have remained in Germany living in a season caring nothing for religion.

Henry and his sister Bertha sailed for America in 1853, landing in New York September 8, from where he went to St. Louis, Missouri. There he found employment with a wholesale drug business. There he also became acquainted with Mormonism. On the morning of December 10, 1854 he happened to hear that Mormons were going to meet in a chapel in the city. Out of curiosity he decided to attend, to see some of the desperate characters he had heard so much about. But as the people gathered, each one greeting him as they entered, he was surprised to find them so friendly and sociable, and so different from what he had heard of them. But he was disappointed in this spirited singing and in the quick way Elder Milo explained the principles of the Gospel, being used to solemn music of the Lutheran Church in Germany and an orthodox Christian minister. The next morning a fellow clerk handed him a copy of Parley P. Pratt’s Voice of Warning, which he read through that night. On being asked how he liked it, he replied he had read many interesting things in it, but could not believe in visits by angels or visions.

At this time he had discarded all religious belief, but was not satisfied with infidelity, and so was ripe for conversion to the truth. As he continued to attend their meetings faithfully, he formed a habit that he continued throughout his life and ever strongly hoped his posterity would adhere to as well. He also continued to read studiously every pamphlet and book he could find in St. Louis having any bearing on the doctrines of the Church. In three months he was thoroughly convinced he had found the truth. But he could not bring himself to the point of being baptized. He prayed earnestly for some manifestation from the Lord concerning this step. His prayers were answered by a dream in which Elder Erastus Snow talked with him and commanded him to be baptized. He further said his companion, Brother Brown, would be the man to do it.

He was baptized March 11, 1855 by Elder William Brown at 7:30 a.m., in a pool of rainwater. In the afternoon Elder Brown confirmed him. April 13, he was made a Deacon, and on May 16 he was ordained to the office of a Priest, on May 13 having preached for the first time. June 17, he baptized his sister Bertha, and on October 11, he was set apart as a missionary to the Cherokee Nation. On October 11, he was set apart to do missionary work under the hand of the President of the Stake.

On October 24, 1855, he settled up his typing and left St. Louis for his mission. Laboring among the Lamanites for four and one-half years, he suffered all manner of hardships and privations; most of the time chills and fever, until his health was almost ruined. He met with some success, baptizing some members and the Church. The authorities of the Church seemed to lose track of the five or six elders in the mission. Inasmuch as he could not get word from the President, Henry decided to ask the Lord in humble prayer if he should leave the mission and go to Zion. His answer came in a dream in which he saw himself in Salt Lake City. He went to President Young and told him he had come without being sent for, but if that was not all right, he would return and finish his mission.

He and Elder Richie started to Zion and on their arrival went to see the President and his dream was literally fulfilled. President Young welcomed them and said they had been expecting them.

On the journey from his mission, Henry fell in with the company of Saints on the plains and became interested in one of them, Mary Bommelli. They had many pleasant walks together ahead of the company and to them it was a very pleasant pilgrimage. They arrived in Salt Lake City August 29, 1860 and on December 14, 1860 they were married.

She was a native of Weingarter, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland, and was born March 10, 1830. She was baptized into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in November, 1854. She emigrated in 1859, going as far as New York City, and in 1860, crossed the plains to Utah territory.

Henry and his wife settled in Ogden. While there, he joined the military organization, being part of infantry. When they first moved to Ogden, he traded his pony for a city lot which was half swamp. Long years after he had disposed of it, it became very valuable, being used for a railroad depot. From Ogden, he moved to Salt Lake City. Up until this time he had never done any hard manual labor, but being very ambitious he preferred any work he would find rather than be idle.

In June, 1862, he began cutting stones on the Temple block for a $1.25 per day after that he did a lot of copying music. At the October conference in 1862, he volunteered to move to Dixie. On May 1, 1863 his first son was born, Henry Elias.

In October, 1862, they started for Dixie taking passage with John Nebeker. After a tedious journey, they arrived about November 23. They got work at Washington, ginning the cotton where they remained until the latter part of January. They then pitched a borrowed tent on the lot which was their home as long as they remained in St. George. He says:

Our earthly possessions were very limited. We all and some clothing, some bedding, and provisions to eat for three months. We had neither team, wagon, cow, or even chickens. I presume we commenced with as little as anyone ever did in St. George. My wife was a good weaver so we exerted ourselves to get a loom, and when we succeeded in this, her faithful and untiring efforts brought us a good many comforts which we could not have obtained in any other way. I cannot speak too highly of my wife Mary, for through her ceaseless energy and untiring labors, we succeeded with the blessing of heaven to gradually work ourselves up out of extreme poverty.

He tried all kinds of hard work such as farming, gardening, adobe making, stone cutting, living and working on the poorest fare until his health was badly impaired. His first job he says was erecting a sod house 16 ft. square covered with willows and dirt. He says that when he accomplish this he felt proud as it was comfortable and they were better fixed than many of their neighbors. November 6, 1863, Louise was born. They also raise some cotton which his wife woven the cloth, to pay for the building of their first adobe home.

He further stated:

Clara was born July 14, 1865, but died July 13, 1866. On May 27, 1868 Edward Christian was born. In September 1868, I was taken violently ill with rheumantics in the back and hip and was confined to my bed for about three weeks. When I recovered from this sickness I secured employment in the St. George office as assistant to Brother Franklin B. Wooley, clerk of the office.

This change of work benefited him.

January, 1869, money was subscribed for starting a co-op store. From this time on Henry found clerical work which he was well prepared to do. About May 1872, he took charge of the store and under his administration built up a very successful business. He continued with the store until he moved to Mexico in 1877. He was one of the few successful operators of co-op stores. This grew and flourished under his administration, paying handsome dividends all the time. When he arrived in Mexico, he started another co-op store on a small scale but it soon doubled and trebled its capital until it became a very profitable institution.

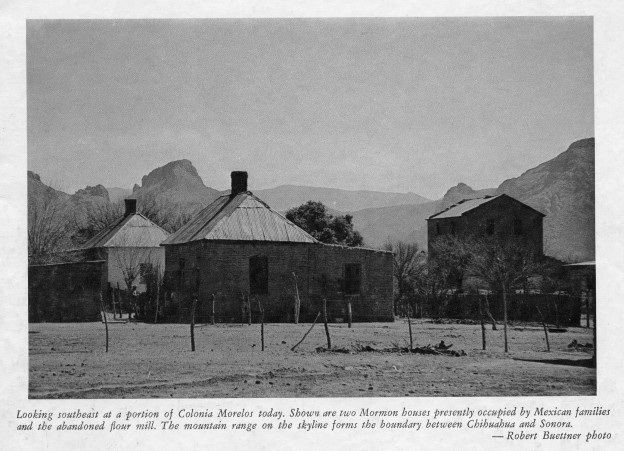

He might have done as many other co-op superintendents have done, bought up stock and weeded out stockholders to his own gain, but he would not do that. He was content to live and let live. The result was that in each case he turned back to the stockholders a flourishing business. He was an honest man in the truest sense of the word. The success in St. George in the mercantile business was repeated in Colonia Juarez.

On August 12, 1872, he married Deseret Faucett, and on August 1, 1874, he received a call to a mission in Switzerland and Germany. August 31, 1874, he left to fill this call, going by way of New York, Liverpool, London, Antwerp, and Cologne. He traveled very extensively in Germany and Switzerland with his sister Clara. He was banished from Germany and went to Berne, Switzerland, where he edited the Church publication, Der Stern, and translated the Doctrine and Covenants into the German language. He also published tracts and a songbook.

Because of his plural marriages, Henry decided to move to Mexico where he could live peacefully. Apostle Snow invited him to go to the Mexican colonies, promising that he would do better in every way and Mexico than he had ever done in St. George, which proved to be the case.

In February 1887, he left for Mexico with the following members of his family: his wife Deseret, Edward Christian, Annie, and Andrew. He started out with one light wagon and one team, traveling by way of Price, Scandlen Ferry, Hackleberry, Mesa, Fort Bowie, San Simon, La Ascencion, Casas Grandes, and Colonia Juarez. We arrived there on April 1, 1887. Father secured two city lots and fenced them and commenced to cultivate and plant trees and vines. He also built a small log house Deseret. Then he left to a fill a call to serve as a missionary in Mexico City.

He had faith in Apostle Snow’s promise to him in which he had said, “If you will take this mission, learn the Spanish language, become acquainted with the people, in the laws and customs of the land, as well as with government officials, and through it all learn how to do business in this land, you will be great blessing to the Saints in Mexico.”

Arriving in Mexico, he began study of the Spanish language, although he was then 50 years of age. Yet, he mastered it to the extent that he could transact business in the language, could take care of legal matters and receive instructions from prominent men of the nation, including President Porfirio Diaz himself, without an interpreter. Later at home in Colonia Juarez, he was able to teach the language both to the students in the school and to adults in night school. So far as meeting the success he had hoped for in his missionary work, however, he was somewhat disappointed.

The following is from his journal:

On account of the return of so many of the Mexican Saints who failed to make a location at Colonia Juarez and who told exaggerated tales of woe and disappointment, it was very difficult to make any headway among the members of the Mexican Mission. Nearly all of them believed the false statements about our colony and a bitter feeling was engendered by many. The consequence was that two of the branches that had at one time been the most flourishing, declared themselves independent of me. In addition, a false prophet arose claiming to believe the book of Mormon but taking all manner of false doctrine. Having a very fluent tongue and being a man of force and energy, he upset quite a number of the members. However, a few remained faithful, it was impossible to make any headway by any of the new converts. While there, one man living in Morelos took quite an interest and applied for baptism. I think I must have converted him for the Lord never did. Being a drunkard, he soon drifted into his old habits and left the Church. Though my mission to Mexico was in some ways unsatisfactory, I believe that as a whole I accomplish what Brother Snow required of me.

Our beloved Apostle and true friend, Erastus Snow, died at Salt Lake City, May 27, 1888. By his death Mexican colonies lost a leader who would greatly have promoted their welfare if he had lived. As it was he had laid the foundation, and his wise counsels are quoted to this day.

Near the close of 1888, there being no new openings and the people of Colonia Juarez being anxious for my return, I turned over the affairs of the mission to John Rogers. I bought a small stock of merchandise for our completed co-op store at Juarez, and then returned, reaching there in company with Annie Snow on December 29, 1888.

I found my family in fair health, except Annie, who was recovering from a severe attack of pneumonia. A frame store having been built, I opened business on January 1, 1889, with a stock of goods of about $1500. At first I opened about two hours in the morning about the same in the evening, working in my lots the remainder of the time. That’s very soon business increased, and my whole time was required. In May 1889, burglars entered the store and got away with about one third of our stock of merchandise. That year, as business was increasing, I sent for my son Edward Christian to help me. He arrived in August, and at once began his work.

August 29, a son named Carlos Fernando, was born. In February, 1890, I went to Mexico City on business for our Colonies.

In April I went to Utah to move my wife, Mary, to Mexico, reaching St. George about the 26. She had been closing out our furniture and I sold one of our water rights to James Andrews for $100 so we had something like $600 to take with us to Mexico. On May 1, 1890, we started for Mexico with myself, wife Mary, Henry, and Ida. Emily, who had married William Snow, son of Erastus Snow, on November 9, 1887, remained in St. George.

We went by team to Milford and by railroad to American Fork, where we visited my sister Bertha.

From American Fork, we went by rail to Deming and from there by team to Colonia Juarez, arriving on May 15, 1890. During the summer this year I built a brick cottage on my lower lot for my wife, Mary and family, who moved into it about November. February, we received a visit from Apostles Moses Thatcher and George Teasdale. Brother Teasdale returned her call you Diaz where he was temporarily located and about May returned with his wife, Ettie, and her two children and lived with us several weeks. He then moved to the Snow house. Later in the season a temporary organization was effected, called the Mexican Mission with George Teasdale as President, and A. F. Macdonald, and Henry Eyring as counselors.

I attended the October Conference in returning, went in company with Brother Moses Thatcher to Manassa, Colorado. There I met sister Georgina Snow Thatcher, who had a home in Manassa. While there I posted up the books of the Mexican Colonization and Agricultural Company. I stopped at the house of brother John Morgan who had since died. On October 3, 1891, my daughter Fernanda Carolina was born.

In 1893, he attended the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple, and participated in meetings held afterwards by Authorities of the Church in the upper rooms of the Temple. The first two of these meetings were to ascertain to what degree the First Presidency was sustained. He among others proved they were in full accord and were willing to give full support. At the last meeting at which they fasted and prayed, it was attended by the largest group, 140 people, ever gathered for that purpose. After prayer, they went into another room to partake of the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper and were filled with rejoicing.

While in Salt Lake City, he met his daughters, Louise and Emily, and two children and returned with them to Sanpete, and from there started for Mexico. Arriving in Colonia Juarez, May 1, 1893, he found a late frost had destroyed the fruit, including the grapes. The second crops of his muscats did very well. That year, he built a frame house for his wife Deseret into which she moved immediately. That same year he went to Mexico City in company with A.F. Macdonald and Meliton Trejo and, together, were able to get a new contract for colonization. They were also allowed a personal interview with President Porfirio Diaz, who treated them very cordially.

In the spring of 1894, he was appointed by Apostles Brigham Young, Jr. and John Henry Smith to go to Chihuahua City to secure better water rights for Colonia Juarez. There he waited three weeks for an interview with the governor, but was then successful in getting from him a letter to the presidente in Casas Grandes asking him to see that the colonists were not curtailed or crippled in their use of water.

In December 1895, Apostle Francis M. Lyman organized the Juarez Stake of Zion. Anthony W. Ivins, who had been set apart in the office of the First Presidency, was made President and Henry Eyring and Helaman Pratt were sustained as his Counselors. In the capacity Henry, with his wife Mary, who had been made Stake Relief Society President, and Elder George Teasdale, visited all the settlements in the stake except for the two most recently organized, Colonia García and Colonia Chuhuichupa. These they visited the following year in company with Helaman Pratt.

Although Henry suffered a slight decline in health about this time, he was able to carry on throughout the years, meeting both civic and ecclesiastical responsibilities and finding time to teach Spanish, help those needing it with legal transactions, and taking care of his store.

It has been remarked by men who knew him best that he never stopped growing until his last day. Father’s word was as good is his bond. In all the years that I, Edward Christian, his son, worked with him, I never knew him to do a small mean being. He was free with his means in all public works. He used splendid clean language, free from slang and petty swearing.

It was, as Miles P. Romney said to me once, ”He has a splendid type of European gentleman.” He was very kind to his wives and children. I never heard him speak an unkind word to one of his wives and he was always kind to his children as well. He had high ideals for education. I think he would have gone to almost any length to help us children become educated. He held high positions in the Church from the beginning and never received a penny for his services. His idea was that if we pay for our services here, we could not expect pay hereafter. He preferred to lay up treasures in heaven and went to his just reward February 10, 1902 in Colonia Juarez.

Edward Christian Eyring, son

Stalwarts South of the Border by Nelle Spilsbury Hatch

pg 152