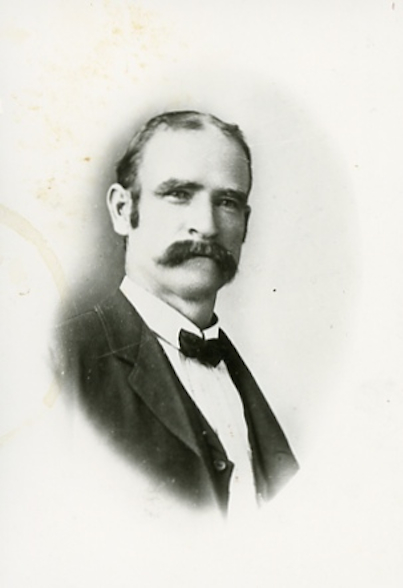

Junius Romney

1878-1971

Born March 12, 1878, in St. George, Utah, Junius Romney was the son of Miles Park and Catherine Cottam Romney.

Miles Park’s father, Miles, had moved to St. George under the direction of Church leaders and was playing a significant role as a builder, supervising, for example, the construction of the tabernacle. Miles Park assisted in that construction as head of the carpentry shop. He had other business interests and civic commitments, most notable in drama, and served in various church administrative capacities. Catherine, Junius’s mother, was born to a family which had settled in St. George in 1862. Because Miles Park had five wives, several of whom had large families, brothers, sisters, and cousins abounded.

When he was three years old, Junius accompanied his his family to St. Johns, Arizona, one of several centers of Mormon settlement on the Little Colorado River. They first settled in town in a log cabin with a dirt floor, later replaced with a nice frame home. The Romney family was in the middle of an intense anti-Mormon campaign to which Miles P. responded vigorously as editor of a newspaper and which forced Catherine and others to flee their homes periodically. This persecution became so intense that Junius and most of his family returned to St. George in 1884.

This second period in St. George was temporary while Miles P. and others investigated places in Mexico to which they could flee for safety. Junius and his family lived with Catherine’s parents, the Cottams, who at the same time furnished a hiding place for Wilford Woodruff who was being pursued by government authorities. To help support the family, Junuius tended cows in the surrounding desert. So hot was the sand at the time that he recollects moving from the shade of one bush to another, crying as he stood on one bare foot and then the other to allow each an opportunity to cool. When he reached eight years of age, he was baptized in the temple font. Then in 1886, Catherine and her children were instructed to join Miles P. and others in Mexico. The Cottams generously outfitted them with clothing and, following blessing from Wilford Woodruff, Junius Romney and the others left for their new home in Mexico.

During January of 1887, they traveled by train to Deming, New Mexico, then by wagon into Mexico. ON the way, Junuius was thrown from the wagon and run over. His ear, torn almost completely from his head, was replaced and bandaged in place by his mother. On arriving in Colonia Juarez, the newcomers joined two of Miles P.’s other families—Annie’s, who was living in a dugout beside the river in the “Old Town,” and Hannah’s, who lived in a house of vertical poles called a “stockade house.” Catherine’s house was their wagon box to which were attached a bowery and a small wooden room.

Life was simple and family centered—simple clothes, straw or husk tick on the beds, a diet of corn, beans, molasses, greens and thinned milk, and occasional treats of wheat flour bread. In his later years, Junius still enjoyed the simplicity of a sweet apple off a tree or a dinner of cheese, bread, and milk.

After about a year in Colonia Juarez, the three Romney wives and the family of Helaman Pratt moved to Cliff Ranch, a small valley along the Piedras Verdes Riverin the mountains. Here they lived for about two years in seclusion. This required independence and innovation. Junius Romney recalls how his mother and the other adults provided religious and intellectual instruction in addition to the necessities of life. Work included herding cows barefoot in the snow and building irrigation systems. Natural greens, potatoes, and grains were staples with treats of molasses cake, nuts and potato pie. In addition to other qualities he may have developed there, Cliff Ranch increased Junius Romney’s appreciation of his family.

In the fall of 1890, the Romney’s returned to Colonia Juarez, and not long thereafter, Junius Romney moved to a farm which his father had purchased about a mile west of Casas Grandes. There, with his Aunt Hannah and her family, he worked for three years and received the benefit of three months’ formal schooling per year in Colonia Juarez.

In his 16th year, Junius Romney became an employee of the Juarez Cooperative Mercantile Institution. This led him into his vocation as a businessman and into a close association with Henry Eyring, the manager. In that occupation, he became acquainted with the Mexican people, merchandising procedures, Mexican law, bookkeeping, Spanish, and the postal service. He soon became postmaster, a position he held for 13 years. Junius later observed how much he owed to Henry Eyring, who also taught frugality through making bags out of newspapers in order to save buying them commercially.

It was during this time that Junius Romney became acquainted with Gertude Stowell, daughter of Brigham and Olive Bybee Stowell. Brigham operated the mill on the east side of the river south of town and owned a cattle ranch north of town. Gertrude grew up willing to work hard, a trait she preserved throughout her life, and was also interested in intellectual activities and things of beauty. After she broke her engagement to another young man, Junius courted her earnestly. His correspondence with her progressed from “Dear Friend” to Dearest Gertrude” and culminated in their marriage in the Salt Lake Temple on October 10, 1900.

Junius Romney continued his work in the Juarez Mercantile as their family began to grow. Olive was born in 1901, Junius Stowell, called J.S., in 1903, and Catherine (Kathleen), in 1905. That Kathleen survived, having been born at only two and one-half pounds while both parents were suffering from typhoid fever, is something of a miracle. Margaret was born in 1909. Catherine, Junius’s mother, lived with them for a time after the death of Miles P. in 1904.

The typhoid fever that both Junius and Gertrude suffered was accompanied with pneumonia for Junius, but after limited professional medical care and extensive aid from family and friends, they recovered.

More important, for Junius, was the fact that an early administration by Church Elders did not heal him. He concluded that the Lord needed to impress him that he indeed had typhoid fever and his eventual recovery indicated that the Lord had a purpose for his life, a purpose he saw fulfilled in his role as leader during the Exodus of 1912. Successful healings from priesthood administration shortly thereafter reinforced this opinion.

The young couple lived in an adobe house directly north of the lot upon which the Anthony W. Ivins house once stood and the Ward building now stands. In about 1906, a substantial brick house, which still stands, was built. The bricks were cooperatively prepared with several other families.

The resulting structure with its clean lines and decorative wooden trim was equal to any similar sized house built in Salt Lake City at the time, and, in fact, reflected the strong North American orientation of the colonists.

Junius continued to work in the Juarez Mercantile store until about 1902. He thereafter worked for the Juarez Tanning and Manufacturing Company until about 1907. He continued as postmaster, handling business from a room made on their front porch. In addition to this work, Junius was very much involved in other business activities such as buying and selling animals and land, and supervising some agricultural production. He handled some legal matters for colonists and taught bookkeeping and Spanish at the Juarez Academy.

For two months during the summer of 1903, while Gertrude tended the post office and their two young children, Junius Romney went to Salt Lake City where he attended the LDS Business College. His studies included penmanship, bookkeeping, and typing. Among his extra-curricular activities were attendance at bicycle races at Saltair, as well as visiting relatives. In addition to the three three-month periods of schooling while he lived on the farm near Casas Grandes, and about three years of taking classes at the Academy just before his marriage, this stay at the business college concluded his formal education.

During these early years of marriage, Junius served as Second Counselor in the Stake Sunday School Superintendency. During a very busy January, 1902, he served as an MIA Missionary in which calling he participated in a flurry of meetings in Colonia Juarez. He also served as Stake Clerk, which with his Sunday School calling, led him to visit throughout the colonies and to become acquainted with the conditions of the Church and the people. He also learned much of Church administration.

Two major recreational activities occurred during these years. The first was a visit in 1904 by Junius Romney and a friend to the World’s Fair in St. Louis. The second was a trip in company with the Stake President, Anthony W. Ivins, into the Sierra Madres where President Ivins owned some land. Junius fished and hunted and, more significantly, enjoyed the association of the man whom he was soon to succeed as Stake President.

As the government of President Diaz came under attack and was eventually defeated by the forces of Francisco I. Madero, the Mormon colonies were drawn into the struggle. Junius processed various damage claims submitted by the colonists to contending parties, and, as President of the Stake, he became directly involved in the aftermath of the death of Juan Sosa, which occurred in Colonia Juarez in 1911. In the Sosa matter, he assisted in hiding colonists who, as deputies, had participated in the shooting. He eventually met with a local judge and sent a letter to President Madero on behalf of the fugitives. This letter at last reached Abraham Gonzales, formerly Governor of Chihuahua and then Secretary of the Interior in Mexico City. Gonzales directed that the prosecution of the Mormon deputies be discontinued. Eventually the matter was forgotten as the military struggle increased in intensity.

Soon after President Ivins was called to be a member of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, John Henry Smith and George F. Richards of the same quorum came to Colonia Juarez to reorganize the Stake. In the meetings of March 7 and 8, 1908, these visiting authorities selected Junius Romney as the new Stake President with Hyrum H. Harris and Charles E. McClellan as Counselors. The visiting authorities indicated that plural marriages were no longer to be performed in Mexico as they had been since 1890. Because he had not been directly involved in these recent plural marriages and was living in monogamy, Junius was a good choice to implement that policy.

As Stake President, Junius traveled to Mexico City to review the missionary work there and at least twice attended general conference in Salt Lake City. He also traveled to Chihuahua City where he talked with the President of Mexico, Porfirio Diaz, who exhibited considerable interest in and affection for the Mormon colonists. The authoritarian government under Diaz and the work of the Mormon colonists were complementary. The government provided the climate in which the Church members could live in relative security with little interference. The colonists contributed to political and social stability and grew outstanding agricultural products, both qualities that Diaz wanted demonstrated to the native Mexicans.

Routine church business was also handled. His correspondence notes action on a possible Branch of the Church near Chihuahua City, operation of the Church auxiliaries with a Stake activity calendar for the four months through August of 1912, concern in one Ward over lagging tithing payments and pride of another Ward over anticipated benefits from a newly completed reservoir. That the Revolution was intruding upon Church work is indicated by the inability of President Romney to obtain signatures of all Ward Bishops on a document, and instructions to avoid purchasing grain from native Mexicans since the soldiers might need it.

Although the tempo of the Revolution demanded increasingly more attention, Junius still pursued his business interests in a way that indicated he intended to stay indefinitely in Mexico. He was involved in agreements to buy and sell land, a proposal to build a fruit cannery in Colonia Juarez, and the purchase of some 715 fruit trees to be planted on his land.

One of the first direct confrontations between the Revolutionaries and Mormons came in February, 1912, with a demand by Enrique Portillo for weapons. Portillo was a local leader of rebels under Pascual Orozco who by that time was opposing Madero. In company with Joseph C. Bentley and Guy C. Wilson, Junius told Portillo that the only way he would get Mormon guns was with smoke coming out of the barrels. After Junius reported this incident to the First Presidency in Salt Lake City, he received a letter from them which he considered very important. The First Presidency approved the action taken, but said that a different set of circumstances might call for a different response. They advised that the foremost concern should be the safety of members of the Church. A letter from Anthony W. Ivins at this time promised no loss of lives if the Saints were faithful. Some, not including Junius, interpreted this to mean that the colonists could always safely remain in Mexico.

Besides the admonition to care for the safety of the colonists, the policy of neutrality urged on the Saints was important to Junius. This policy was directed to all U. S. citizens from authorities in Washington, D.C. Moreover, the General Authorities advocated neutrality for Church members in Mexico. Regardless of personal feelings, Junius and other leaders attempted to be neutral. This was not an easy policy to follow since soldiers from both sides often forcibly requisitioned horses and other supplies. During the early stages of the Revolution, the soldiers were urged to respect neutrality.

While attempting to remain neutral, the colonists recognized a need to obtain weapons equal in quality to those possessed by the warring factions around them. Accordingly, the Stake leaders attempted unsuccessfully to import high powered rifles in December of 1911. Then in April, 1912, after the U.S. embargo was proclaimed, rifles were smuggled in and distributed to the various colonies from Junius’s home in Colonia Juarez.

After initial success against the government, Orozco was defeated in several battles in May, 1912, and retreated northward toward the colonies. At the same time, Mexicans responded to the killing of a Mexican, surprised during a robbery in Colonia Diaz, by killing James Harvey, a colonist. President Romney in company with several Mexican officials from Casas Grandes rode in a buggy to Colonia Diaz and defused the threatening situation. This experience further impressed Junius with the explosive conditions in which they found themselves and the danger of resorting to an armed defense. As a result, he reaffirmed his belief in the policy of neutrality and the necessity of the Mormons getting through the conflict with a minimal loss of life.

Junius wrote to the First Presidency requesting instruction on what to do and asking that Anthony W. Ivins be sent to the colonies to counsel with them. The First Presidency told Junius to do what he thought best after counseling with other Church leaders in the Stake. Elder Ivins traveled to the colonies and returned to El Paso where he remained throughout the Exodus.

After being defeated by federal forces in early July, 1912, the Orozco rebels moved to El Paso where they made their headquarters. This was usually a place where Revolutionaries could be resupplied with arms and ammunition, but because of the U. S. embargo, Orozco was unable to rebuild his army. So the rebels turned to the Mormon colonists who, they believed, had weapons they could obtain.

General Salazar, a local rebel leader, called Junius to his headquarters in Casas Grandes and there demanded a list of the colonists’ guns. After consultation with the leaders in Colonia Juarez and Colonia Dublan, Junius requested the information from each colony.

Faced with this increased pressure, representatives from throughout the colonies met with the Stake Presidency to decide how to proceed. The group decided to continue to pursue a policy of neutrality and to act unitedly under the direction of the Stake Presidency.

On July 13, 1912, when news reached Colonia Juarez that rebels in Colonia Diaz were demanding guns from the colonists, a meeting of eleven local men and two members of the Stake Presidency was convened at Junius’s home. The group sent messengers to Colonia Diaz with letters previously issued by rebel leaders urging respect for the neutrality of the Mormons. Junius Romney and Hyrum Harris of the Stake Presidency were instructed to confer with General Salazar to persuade him to call off the rebels. Junius prepared a letter to General Orozco in EI Paso which he sent with Ed Richardson.

That same night Junius and Hyrum Harris rode to Casas Grandes where they located General Salazar. Having prevailed upon a guard to awake the general, Romney described the crisis. Salazar lashed out at the rebel leader in Colonia Diaz, saying that he should not have made that demand, todavia no (not yet). Junius reports that those last two words caused a chill to run up his back, since it seemed to be the general’s intention to sometime require weapons of the colonists. Such a demand, Junius foresaw, would perpetrate a crisis. Romney and Harris received an order from Salazar which they took to Colonia Dublan for delivery to Colonia Diaz.

The next day, Junius traveled by train to El Paso to confer with Elder Ivins. On the way he had a conversation with General Salazar who said he intended to do something to force the U.S. to intervene militarily in the Revolution. In El Paso, Elder Ivins seemed to think that Junius was overly concerned. Still, they jointly sent a telegram to the First Presidency requesting instructions. The reply said that “the course to be pursued by our people in Mexico must be determined by yourself, Romney and the leading men of the Juarez Stake.” Romney was looking for specific instructions, but received none. He later reflected that if the Lord intended to have his people removed from Mexico, it was better that he, rather than Elder Ivins who had put his life into building the colonies, should lead that evacuation. Although Ivins visited the colonies for several days during the next two weeks, he gave no more specific instructions on what to do.

Orson P. Brown, the colonists’ representative in El Paso, wrote Junius that the State Department had indicated that the Mormons could not expect U.S. governmental support in the event they defended themselves. Brown predicted that the colonists would have to leave their homes.

Fearing the worst, Junius wrote a letter on July 24, advising the mountain colonies to be prepared to leave on a moment’s notice, should the need arise.

Two days later, Junius, in company with four other colonists, traveled to Casas Grandes for a meeting with General Salazar. The general and his aid, Demetrio Ponce, a Mexican who lived among the Mormons, ordered Junius Romney and Henry E. Bowman to deliver Mormon owned guns and ammunition to the rebels. Junius refused to do so and was supported in his decision by Bowman. Bowman’s support was further evidence to Junius that the Lord was directing things since such support was essential to the later evacuation, and the older man had previously been somewhat critical of the young Stake President. Salazar then directed some soldiers to accompany the Mormons to Colonia Dublan where they were ordered to collect weapons, by force if necessary.

In Dublan, Junius Romney conferred with Bishop Thurber and other men. They decided that some compliance was required, so instructions were sent for colonists to bring in their poorest weapons. The rebels were temporarily pacified when these deliveries were made at the schoolhouse.

In the same meeting, it was decided to send the Mormon women and children to EI Paso for their safety. Henry Bowman left at once for Texas to arrange for their arrival and a few colonists departed with him that very day. Junius composed a letter to Colonia Diaz describing what had occurred and directing the colonists in that community to follow the same procedure for evacuation.

That same evening, Romney returned to Colonia Juarez where he joined a meeting of the men already in progress. Bishop Joseph C. Bentley and others were not in favor of anyone leaving the colonies, but after some discussion and a recommendation from President Romney that they evacuate their women and children, he and the others agreed to comply and to urge others to do the same. Those at the meeting also agreed to relinquish their poorest weapons to the rebels.

On Sunday, July 28, some weapons and ammunition from the Juarez colonists were delivered at the bandstand to the rebels. Junius sent messages to the mountain colonies of Colonia Pacheco, Garcia, and Chuhuichupa advising them to be prepared to give up some of their weapons and to send their women and children to EI Paso. He told his wife, Gertrude, that the Bishop was in charge of the evacuation and would help them leave. He bid his family farewell and departed to Casas Grandes to meet with General Salazar.

The actions on July 27 and 28 left the colonies occupied only by adult men. Each town was furnished with a small contingent of rebel soldiers who were responsible for keeping the peace and protecting the colonists who had presumably relinquished their weapons. During the next few days of relative calm, Junius wrote to the various colonies to apprise them of the situation and to advise them to act moderately, with the highest priority being given to safeguarding the lives of the men.

The situation took a turn for the worse when other rebel soldiers began moving through the colonies after having been defeated in a battle with the federals in Sonora on July 31. Uncertain about the intentions of these new arrivals, Junius and other men met in the store on August 2 and decided to call a general meeting for that night. Junius and some others understood that the night meeting was to decide on a course of action. However, as men were notified of the meeting, some understood that they were to leave town that night and go into the mountains.

That night, as Junius started toward the designated meeting place north of town, he was told that some men had already gone into the mountains. He was convinced that the rebels in town would conclude that those who left were on their way to join the federals and any men who remained would be in serious danger. Junius was unable to consult with other leaders as he had previously done, but what he needed to do seemed clear to him. His decision was to have all the men remaining in the colonies congregate at the Stairs, a previously designated site in the mountains farther up the Piedras Verdes River. Then he sat under a lantern in the bottom of the Macdonald Springs Canyon and prepared letters for Colonia Dublan and the mountain colonies, instructing the men to meet at once at the Stairs.

On the other side of the river, a significant number of the Juarez men had met at the designated site north of town, but when they did not find President Romney or the others there, they returned to their homes. When Junius discovered this later in the morning of August 3, he attempted to countermand his instructions to Dublan, but the men had already left. Later, Junius, his brother Park, and Samuel B. McClellan encountered these Dublan men and accompanied them to the Stairs.

The men who remained in Juarez, including Bishop Bentley, initially decided to go to the Stairs, but when the rebels were frightened away by the news of approaching federals, they wrote to those in the mountains expecting that they would return to the colonies. Later, when the men in town received pointed instructions from President Romney that they should go to the Stairs, Bishop Bentley and others complied.

After a preliminary meeting of the Church leaders at the Stairs, a mass meeting of all the men was held on August 5. At that time, those who had most recently arrived from Colonia Juarez urged the men to return to their homes. A majority of those there, including President Junius Romney, favored going to the United States. Junius had several reasons for his decision. He had witnessed the strong anti-American feeling among the Mexicans. He recognized the danger of international repercussions if American citizens were killed in Mexico. He wanted the smuggled guns they were carrying to reach the U.S. A vote to leave was made unanimous. The movement was made under the military leadership of Albert D. Thurber and the men crossed into New Mexico on August 9, 1912.

The fact that the colonists were out of Mexico did not release Junius as Stake President. He continued such functions as issuing recommends, counseling Ward leaders, and gathering information to help him decide what future action he would suggest. He interviewed the colonists themselves, talked with generals of the federal army, and took a three week trip back into Mexico.

The overall supervision of the refugees came under the control of a committee which included various colonists, Junius Romney, Anthony W. Ivins, and other Church representatives. This committee first concerned itself with the evacuation of the colonists in Sonora. Quite independently of the Chihuahua colonists, they evacuated their homes and were in the U.S. by the end of August.

The committee also considered whether the colonies should be reoccupied. Some returned soon after they left, mostly to recover cattle and other property. It was eventually decided that the colonists should be released from any Church obligation to live in Mexico, so that each family could make its own decision. Junius and his family decided not to return.

Gertrude and their four children had initially stayed in a Lumberyard in EI Paso with many others, but they soon moved to a single-room apartment. In the winter of 1912, they moved to Los Angeles with one of Junius’s brothers.

Junius traveled to Salt Lake City where he reported his stewardship to a meeting of the First Presidency and Quorum of Twelve. He reports that he “assured President Smith that I had lived up to the best light that I had been able to receive and consequently if the move was not right I disavowed any responsibility inasmuch as I had lived up to the best inspiration I could get and had fearlessly discharged my duty as I saw it in every trying situation which had arisen.” After hearing this report as well as those of other men and assessing other information they possessed, the General Authorities decided to release Junius as Stake President and to dissolve the Juarez Stake.

While in Salt Lake City, Junius was convinced by Lorenzo Stohl of the Beneficial Life Insurance Company that he ought to try selling life insurance. Junius was dubious about this proposal, but while he traveled on the train back to Mexico, he diligently studied the material he was furnished. Shortly after arriving in El Paso, he was confronted by his brother, Orin, and D. B. Farnsworth, who were looking for a particular Beneficial agent. Junius Romney identified himself as an agent and immediately embarked on a career in which he would be a marked success. During his first year of this work he saw his family only twice, a condition he deplored, but he was determined to succeed. He learned of a contest with a $300 prize for which he would have to sell $60,000 in insurance before the end of 1912. When he won, Junius endorsed the check directly to a creditor to whom he owed money for the purchase of land in Mexico. In the next year, he won prizes totaling $550, which he likewise applied on his debts. Not only did his work help him support his family, but it also resulted in his being given the job of superintendent of agents for Beneficial Life, a position he held for ten years.

By the end of 1913, Junius was able to move his family from Los Angeles to a rented home in Salt Lake City, and six years later, to a home they purchased on Douglas Street on the east side of Salt Lake City. To the four children they brought with them out of Mexico were later added two sons, Eldon and Paul.

While most of Junius’s time during these years after the Exodus was spent in selling insurance, he continued to be concerned with those he knew in Mexico. One project in which he took considerable pride was a resettlement project along the Gila River in Arizona. With Ed Lunt, he borrowed money from Beneficial Life to buy land which was divided into twenty and forty acre parcels and sold with little or no down payment to families from the colonies.

In order to spend more time with his family, Junius left Beneficial Life. Following work in several sales ventures and a few years handling real estate for Zion’s Savings Bank, he became manager of State Building and Loan Association in 1927. He continued in that position until 1957 when his age and ill health compelled retirement. Under his management, the company had expanded to Hawaii and became a leading financial institution in Utah. As part of this work, he sold sufficient insurance to be a member of the Kansas City Life Million Dollar Roundtable three times. He was also involved in various other business enterprises, often in real estate in partnership with others.

He continued to be a faithful Church member throughout his life. He served in various Ward and Stake positions, including the Stake High Council, and as a temple worker in his later years. In later years he suffered from a variety of ailments, perhaps the most serious of which was the loss of his sight. Because he was a man of action, this was especially difficult for him. He was also much troubled by the loss of his wife who served as his companion for sixty-five years in mortality.

He was always very thoughtful of friends and neighbors, as well as his family. As he grew older he expanded his philanthropy. Probably his most noted gift was a rather expensive machine to be used in open heart surgery at the Primary Children’s Hospital.

He kept his sense of humor. For his ninetieth birthday celebration, he appeared in a rather nice hair piece. His family cautiously complimented him on his youthful appearance until the joke became apparent. At that time no one laughed more heartily than Junius.

As his health failed, he began in the late 1950s to talk and write more about the colonies. He dictated and wrote several separate reminiscences about people and events and he gave some talks centering on the Exodus from Mexico to Church groups in the Salt Lake City area. Finally, in 1957, he returned to the colonies. He was interested in reliving that part of his life, but more important to him was explaining it to others, which he did by distributing copies of one of his talks.

When he died in 1971 at ninety-three years of age, he left a significant heritage. His impact on the Mormon colonies was monumental. In business he was a personal success and a builder. In the Church he was a faithful member and significant leader. Among many he was a friend and benefactor.

To his six children, thirty grandchildren, and forty-four great-grandchildren alive at his death, he was a living symbol of much that is good about life.

Joseph Romney, grandson

Stalwarts South of the Border, Nelle Spilsbury Hatch

Page 579