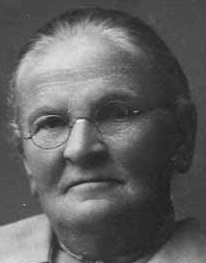

Martha Cragun Cox

(1852 -1932)

Martha Cragun Cox was born March 3, 1852 in the Mill Creek Ward, Salt Lake County, Utah. Her father, James Cragun, was a descendent of Patrick Cragun, born in Ireland, who came to America, settling in Massachusetts. Family tradition has it that in his early manhood he was one of the “Indians” threw the English tea overboard in Boston harbor.

Martha’s mother Elenor Lane, a granddaughter of Lambert Lane who was born in England and emigrated to America with his parents when he was about 12 years of age.

Martha’s parents joined the Mormon Church in 1843 and arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1849. They received the call to pioneer the Dixie, Utah country in 1862. As a girl, Martha learned to leave on her mother’s loom. She made cloth for her own dresses and earned a little money weaving for other people. Quoting from her “Reminiscences,” we learn of an experience that had a profound effect on her life:

One day I was taking from the loom of piece that I had woven for a pair of pants for Brother Jeffreys, a cultivated English gentleman. It had been made from nappy yarn and I told him it did not reflect credit on the weaver. “Oh, well,” he said, “twill only be for a little while we will need it. Twill soon be worn out and then my nappy cloth and the weaver’s work will be forgotten and the weaver too. Though she becomes round shouldered over the loom in trying to serve people with good cloth, (she) will wear out and be forgotten and no one will know that she wove.” These words fell on me solemn-like and prophetic and I pondered them deeply. “What profit is there finally,” I said to myself, “in all this round of never ceasing labor? Weaving cloth to buy dresses to wear out. When my day is past, my warp and woof in life and labors ended and my body gone to rest in the grave, what is there to mark the ground in which I trod? Nothing!” And the thought maybe weep.

I went to McCarty (her brother-in-law James McCarty) and told him what brother Jeffreys had said to me. What can I do that my work and myself will not be forgotten, I asked. He answered “You might plant.” To this I replied that the day would come that our neighbor with all his fine trees, flowers, vegetables, etc., that he had given to St. George would be forgotten by the people and his fine gardens vanished. “Plant in the minds of men and the harvest will be different,” he said. “Every wholesome thought you succeed in planting in the mind of a little child will grow and bear eternal fruit that will give you such joy that you will not ask to be remembered.” His words, though they enlightened, brought to me an awful sadness of soul. I was so ignorant. I saw that I had hitherto lacked ambition for I had been content to dance, laugh, and sleep my leisure time away, never supposing that I might reach a higher plane than that which enabled me to support and clothe myself.

Opportunities for schooling in those pioneer days were very limited and books were not plentiful, but Martha read everything she could find. She kept a list of words of which she wanted to learn the meaning and pronunciation. She would quiz available people for information, including strangers passing through the country, cowboys, miners, old timers. She started teaching school in her middle teens and taught school for 60 years of her life.

Martha married Isaiah Cox December 6, 1869 and became the mother of eight children, five of whom lived to raise families of their own. Isaiah died April 11, 1896 in St. George, Utah.

Martha taught school in Bunkerville, Nevada until 1901, then she went to Mexico to be with her daughters, Rose Bunker, Geneva, and Evelyn. She traveled by way of team and wagon with some of the David F. Stout family. Arriving on the Mexican border, they made camp and stayed for some time in Naco, Sonora. Living there was a family of Indians of the Yaqui tribe. In Martha’s writing she said, “This family of Yaquis were the finest of the human race and looks. The woman who was the honored mother of a large brood had splendid features. In fact, I thought as I looked at her that she was the noblest looking woman in face and form I’ve ever seen.”

Martha had deep sympathy and love for all the Indian tribes. When just a young girl she listened many times in the town of Santa Clara, Utah, to Jacob Hamblin relate his incidents and experiences among the Indian tribes. She felt sure the Walker War trouble in Utah came about because white men broke their promises to the Indians.

Martha taught school in Colonia Diaz in the winter of 1901-1902. The 1902 the family moved to Colonia Morelos in Sonora. By 1906 Martha had moved to Colonia Juarez and for several years taught the Mexican children there. The class was held in the rock basement of the schoolhouse. When Bishop Joseph C. Bentley informed her that the people of Juarez refused to furnish funds to maintain the Mexican school any longer, she was astonished. The Bishop, too was grieved over the condition. “It is better,” he said, “for us to educate them than to try to control a hoard of uneducated ones.” On visiting the home of a Mexican family Martha met the mother, an intelligent woman who spoke her mind on the closing of the Mexican classes. “You Mormons,” she said, “came her poor, you were good people. You teach our little children, we work for you, wash, scrum, anything. You are now rich, you got your riches in our country, now you say you do nothing for us, not teach our children, we are fit only to do your work. You will treat us right or we will in a little while drive you out of our country.” The woman knew more than Martha at the time thought she knew.

Martha taught school in Guadalupe, Chihuahua, the last year or so before the Exodus. Returning to the States, Martha joined her family members including her two sons Edward and Frank Cox and their families. Again she taught school in Utah and Nevada for many years before moving to Salt Lake City where she worked in the LDS Temple as recorder and did other services there. She also taught classes in the next branch of the church, and the MIA and the Relief Society.

In 1928 she commenced writing a biographical record of her life entitled “Reminisces of Martha Cox.” This record ran to 300 handwritten pages, well done and very legible. The journey to Mexico, she writes:

… was the commencement of what I term the fifth chapter of my life. The first being my childhood to adult period. The second chapter, the time from my entering marriage until our family came separated. My third chapter seemed to be proper to my life on the Muddy, in Nevada, comprising nearly 10 years being instrumental in acquiring over 300 acres of good farmland on which the town of Overton was built. The fourth chapter might be my years in Bunkerville and the fifth of our lives in Mexico.

A six chapter, consisting of the 20 years after the Exodus from Mexico, might have been added.

Martha died at 80 years of age on November 30, 1932 in Salt Lake City and was buried there.

Emerald W. Stout, grandson

Stalwarts South of the Border page 123

A longer account of Martha’s life taken from her 300 page autobiography can be found here:

Mike had this question after reading Martha Creagun Cox.

I’m loving the story of Martha Cragun Cox – I’ve printed out the longer Lavinia Andersen piece and am reading it now…..Her story about the Mexican mother telling her that the Mormons saw them as only fit to work for them sort of answers some of the questions I’ve had about colonist/Mexican relationships. I’ve gotten the feeling in my reading that there was quite a bit of resentment that built up over the years between the Mormon settlers and the locals. Why else would the locals destroy the homes we abandoned during the Exodus? Not occupy them, or simply steal them – but utterly lay waste to the homes and the furnishings! That seems to me to be a “crime of passion” – and could be explained by anger or jealousy directed at the colonists.

Mike,

Here is a simplified, overgeneralization to help answer your questions.

The feudal-like hacienda system the Spanish instituted in New Spain created surfs or peons of the rural populations.

After 300 years of being crushed by feudalism, nothing changed for the average Mexican. Even with the adoption of a constitution, it took the Revolution for the people to throw off the yolk of old system.

Much of the resentments came from the deep-rooted hatred of anyone seen as being of the rich or prosperous class. The Mormon colonists were viewed as Americans growing rich off Mexican land and people.

Many of the Revolutionary forces were from outside of the Colonies area and had never interacted with the Mormons. These roving armies and bandits lived off the land and pillaged whatever they needed to keep the armies moving. Whenever a soldier stole something out of spite it was generally overlooked by the army generals because “the rich gringos didn’t need it or earn it anyway.” There are however, stories of colonists leaving their houses, farms, and ranches in the care of trusted Mexican ranch hands who acted as stewards, taking the best care possible in those difficult times.

With that said, there were locals who took advantage of the situation, pilfering Mormon property and worse. These people saw themselves as exacting revenge for some previous perceived slight.

Unfortunately, all the resentments didn’t disappear with the end of the Revolution. There is still an undercurrent of resentment among some of the local Mexican population in the colonies and Nuevo Casas Grandes. Over the years these resentments boil to the surface.

In the mid-1960’s my wife’s grandfather and two uncles were shot (one uncle died) in a confrontation when a local Mexican family became jealous of property owned by my wife’s grandfather.

The drug cartel problems of 2008 – 2009 were difficult times for the Mormon colonists marked by two kidnappings, extortion attempts, and some colonists being threatened.

Currently a Colonia Juarez family is embroiled in a difficult legal battle to keep longtime-owned family land from squatters who claim to have rights to it.

It should be said that just as during the Mexican Revolution, much (not all) of the violence was conducted by people coming from outside of the local citizens of the Colonia Juarez and Nuevo Casas Grandes areas.

Notwithstanding times of upheaval, the 130 years since the Mormon Colonies were first settled have been peaceful. The colonists have been able to live in peace with a spirit of mutual respect with their native Mexican neighbors both Mormon and non-Mormon.